Workforce of Today and Tomorrow: The Economics of Tennessee’s Child Care Crisis

If you’re a Tennessean, the child care crisis impacts you. We have the numbers to prove it.

Our 2022 report, “Workforce of Today and Tomorrow: The Economics of Tennessee’s Child Care Crisis” delivers unprecedented insight into the adverse economic impacts of Tennessee’s child care system dysfunction. The consequences: $2.6 billion annually in lost earnings and revenue.

Acknowledgements

About this Report

This report was produced by Tennesseans for Quality Early Education (TQEE), with support from Clive Belfield, Ph.D., and Zogby Analytics.

Tennesseans for Quality Early Education is a nonpartisan coalition of Tennesseans fighting to ensure our children get the quality early care and education they need to power our state’s future. Learn more at tqee.org.

Clive Belfield, Ph.D., is a Professor of Economics at the City University of New York and an economist with the Center for Benefit-Cost Studies in Education, University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. He was commissioned by TQEE to produce The Economic Losses from Inadequate Child Care for Working Families in Tennessee on which this report is based.

Zogby Analytics was commissioned by TQEE to conduct a new survey of 2,507 Tennessee parents with a child under age 9. The survey is large-scale, new (administered June 23, 2022 through August 1, 2022), and has a sampling frame that matches the Tennessee demographics (race, age, family size) for households with a child under age 9, labor market conditions in Tennessee (earnings, sector of work), and regional populations. Based on a confidence interval of 95 percent, the margin of error for the 2,507 surveys is +/- 2.0 percentage points. Analysis in this report is based on a subset of the statewide sample of parents or guardians working or actively looking for work who have at least one child under age 6 in Tennessee. This representative subset of Tennessee parents has a sample size of 1,297. In addition, oversampling by region was undertaken to ensure sample sizes were sufficient for precise estimates of the impacts by region. The regional analysis is based on the original sample and additional regional oversampling.

Sponsors

- Baker Donelson

- Ballad Health

- Baptist Memorial Healthcare Corporation

- Benwood Foundation

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee

- Bristol Chamber of Commerce

- Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce

- First Horizon Bank

- Greater Jackson Chamber

- Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce

- Hyde Family Foundation

- Joe C. Davis Foundation

- Johnson City Chamber of Commerce

- Kingsport Chamber of Commerce

- Knoxville Chamber

- McNairy County EDC and Chamber of Commerce

- Memphis Tomorrow

- Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

- PNC Bank

- Scarlett Family Foundation

- Tennessee Business Roundtable

- Tennessee Chamber of Commerce

- The Healing Trust

- The Urban Child Institute

A Critical Support for Today’s Workforce

Pre-pandemic, child care was a growing crisis for families and our economy.1 Fast forward to today, Tennessee’s working parents of young children continue to struggle to find and afford child care. For Tennessee employers the situation is likewise acute, with the child care crisis exacerbating the growing labor force shortage.

Pre-pandemic, child care was a growing crisis for families and our economy.1 Fast forward to today, Tennessee’s working parents of young children continue to struggle to find and afford child care. For Tennessee employers the situation is likewise acute, with the child care crisis exacerbating the growing labor force shortage.

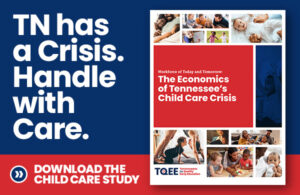

The topline findings of a new study that examined adverse economic impacts of inadequate child care on Tennessee parents, businesses and taxpayers reveals $2.6 billion annually in lost earnings and revenue.

The study, conducted by Tennesseans for Quality Early Education (TQEE), analyzed survey results from 1,297 working parents with children under age 6 to determine how child care challenges adversely affect workforce participation and productivity, and quantifies the resulting economic impact.2

Tennessee Child Care Crisis: What Parents Revealed

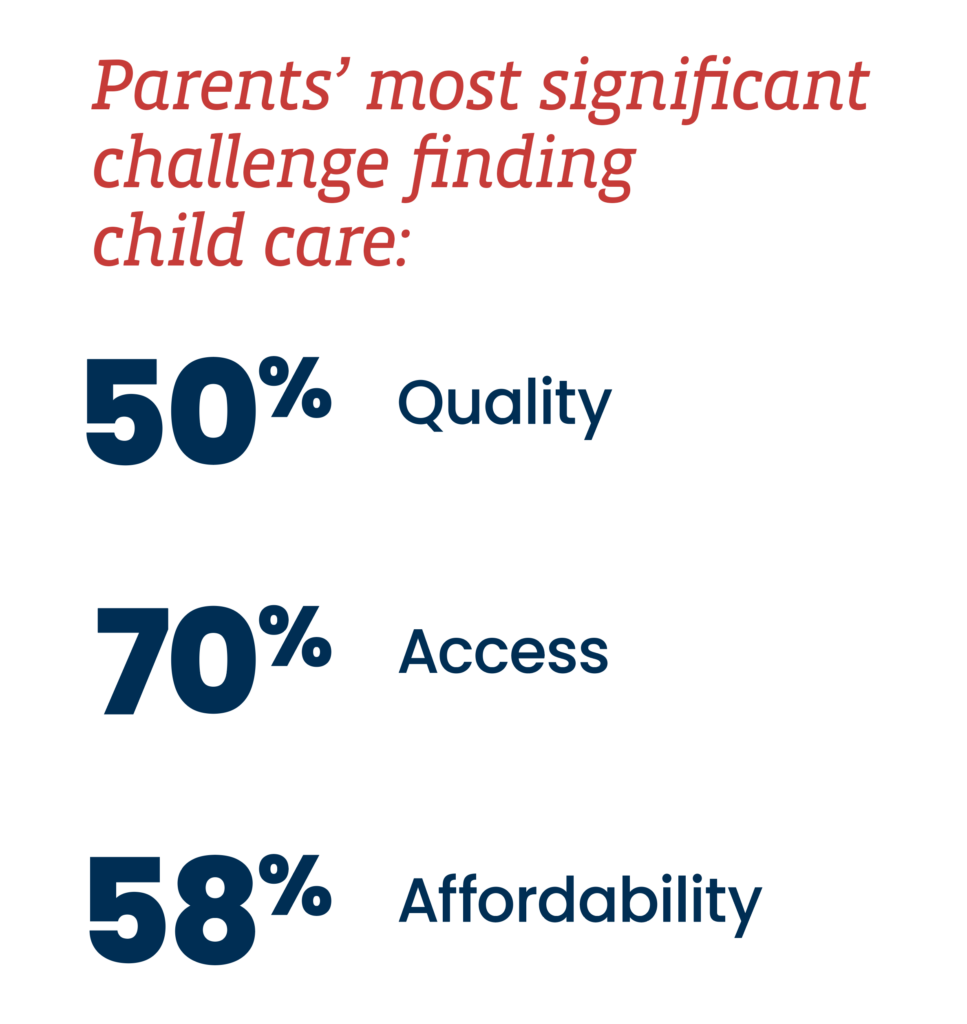

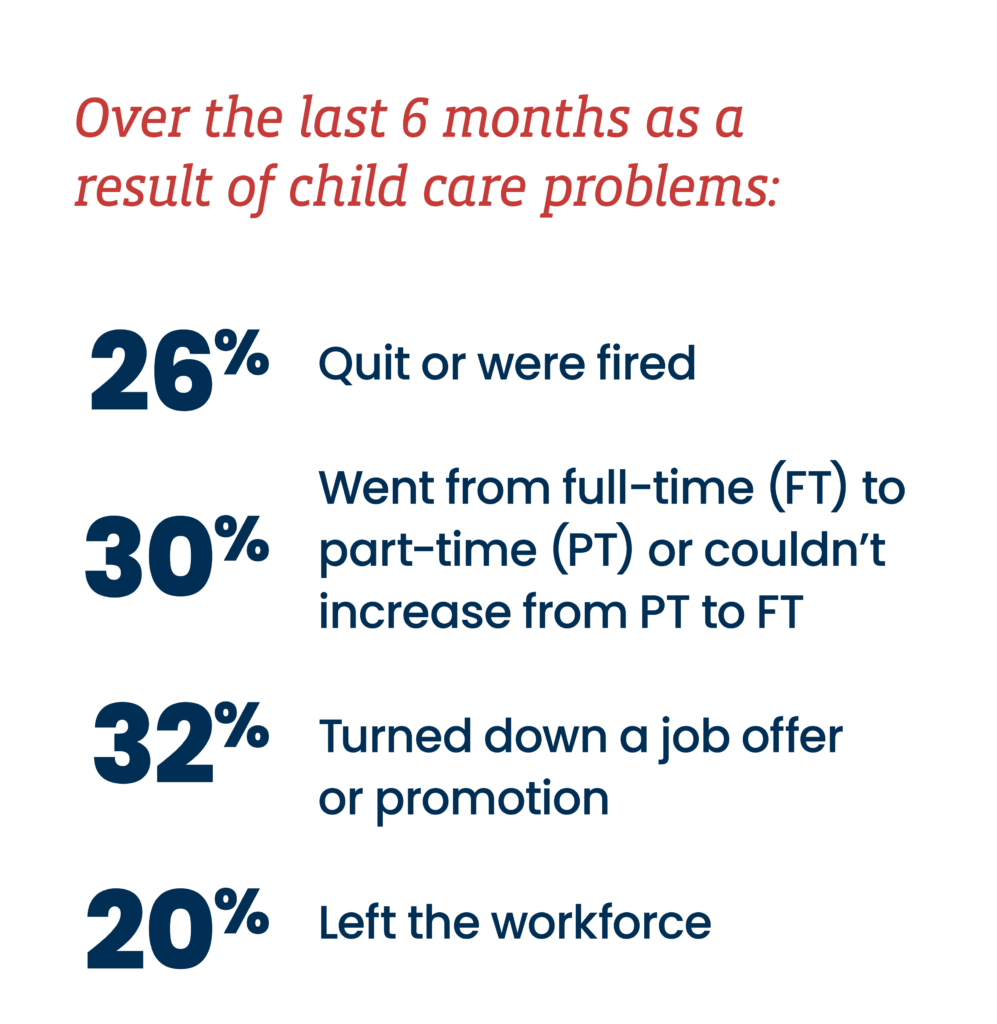

More than 80 percent of working parents reported employment disruptions due to inadequate child care, citing affordability, quality and access as major challenges. Many reported recently quitting, being fired or turning down a job offer or promotion as a result of child care problems. And one in five stopped seeking employment altogether.

The vast majority of Tennessee parents need to work in order to put food on the table for their families, with 72 percent of those surveyed reporting they can’t afford not to work. When families don’t have the child care they need, it affects their household financial stability while also permeating our economy.

Working Tennessee parents and their families are hit hardest, with annual reduced earnings of $1.65 billion. Employers in turn experienced losses of $497 million from lower productivity, reduced revenue, increased hiring and retention costs and, ultimately, lost profits. Finally, the economic impact on families and employers resulted in lower consumption of taxable goods, lower profit margins, and ultimately reduced tax revenues of approximately $413 million per year.

Laying the Early Childhood Education Foundation for Tomorrow’s Workforce

While child care is an essential support for today’s workforce, it also has a significant impact on the development of our children.

Annually over the past decade or so, roughly 300,000 Tennessee children under the age of 6 have all available parents in the workforce.3 In other words, about two-thirds of Tennessee children may spend a substantial portion of the most consequential phase of human development – their first five years – in some form of child care. Therefore, the quality of that care will have profound implications for school readiness and, in turn, the workforce of tomorrow.

We tend to think of K-12 school as where children learn. In fact, the brain develops more in the first five years of life than any other time, with rapidly expanding neural connections “wiring” the brain for future learning, behavior and health.4 Regardless of the setting, whether at home with parents or in care with nonparental caregivers, it’s the quality of care during the early years that determines whether a child’s developing brain provides a weak or strong foundation for future learning and development.

The Economics of Human Potential

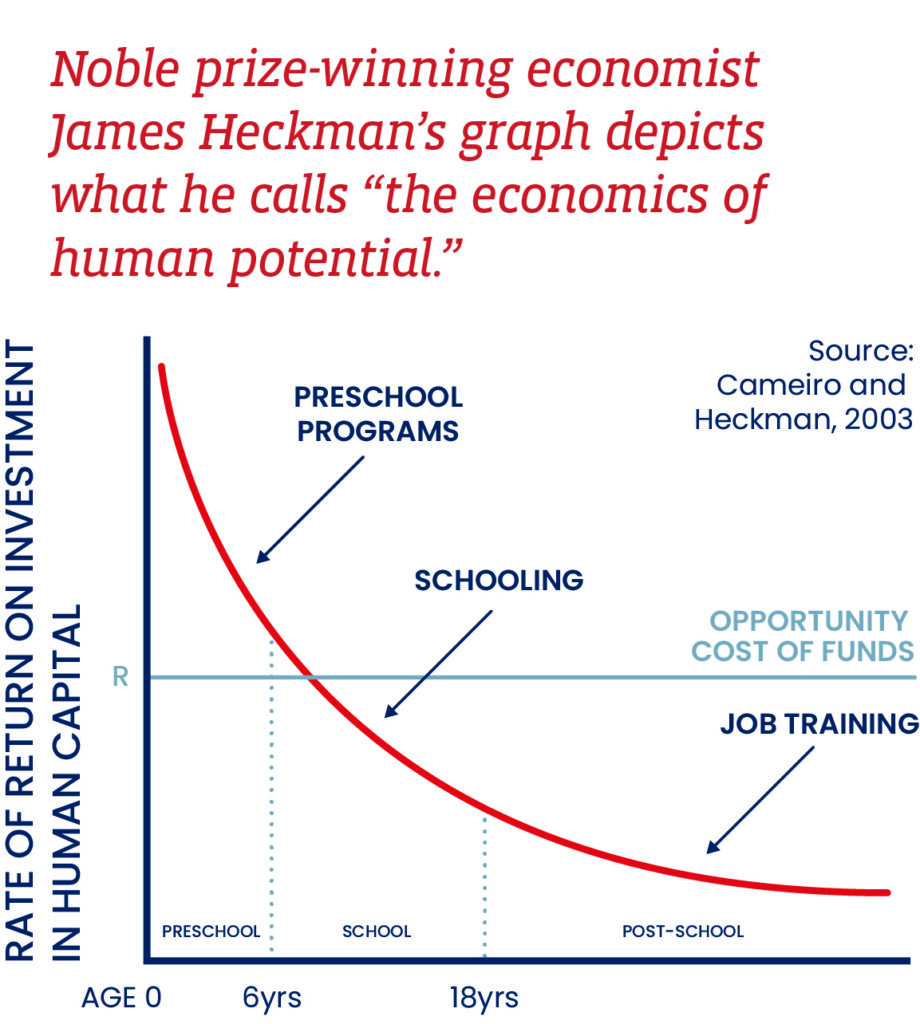

Given the outsized role of early childhood in human development, it’s not surprising that economists have documented a significant return on investment in high-quality early care and education programs. Noble prizewinning economist James Heckman’s graph depicts what he calls “the economics of human potential.”

A broad set of skills – from language to “soft” skills – start developing in children’s first months of life and form the foundation for acquiring additional higher-level skills later. For example, a child develops early language skills beginning in infancy, which help her learn to read a few years later, which in turn equips her to read to learn throughout her lifetime. Similarly, in their earliest years children develop “executive function” and “self-regulation”, which enable skills like persevering on a task, solving problems, building relationships, and managing emotions and impulses. These skills are crucial to later school and work success.5 As Heckman concludes in The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children, “[r]eturns are highest for investments made at younger ages” while “remedial investments are often prohibitively costly.”6

A broad set of skills – from language to “soft” skills – start developing in children’s first months of life and form the foundation for acquiring additional higher-level skills later. For example, a child develops early language skills beginning in infancy, which help her learn to read a few years later, which in turn equips her to read to learn throughout her lifetime. Similarly, in their earliest years children develop “executive function” and “self-regulation”, which enable skills like persevering on a task, solving problems, building relationships, and managing emotions and impulses. These skills are crucial to later school and work success.5 As Heckman concludes in The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children, “[r]eturns are highest for investments made at younger ages” while “remedial investments are often prohibitively costly.”6

Economists Art Rolnick and Rob Grunewald at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis also found that investments in early childhood result in better academic outcomes; improved public health; less crime; and more educated, skilled workers. In calculating the economic impact of those societal benefits, they found a public return of up to 16 percent per year.7

Quality Child Care is Crucial

To capture those returns, the child care must be high quality. Quality child “care,” regardless of the setting, is in fact early education. It provides a safe, supportive environment that promotes the development of cognitive and soft skills necessary for success in school and beyond. It’s interaction-driven, occurring through consistent, Serve and Return engagement with nurturing caregivers who skillfully engage children in ongoing, language-rich conversations and employ other developmentally appropriate care and teaching practices.8 In short, high-quality child care facilitates early learning, and as with K-12 education, depends on the educator.

Why Can’t Families Access the Quality Child Care They Need?

Quality Child Care is Unaffordable for Most Tennessee Families

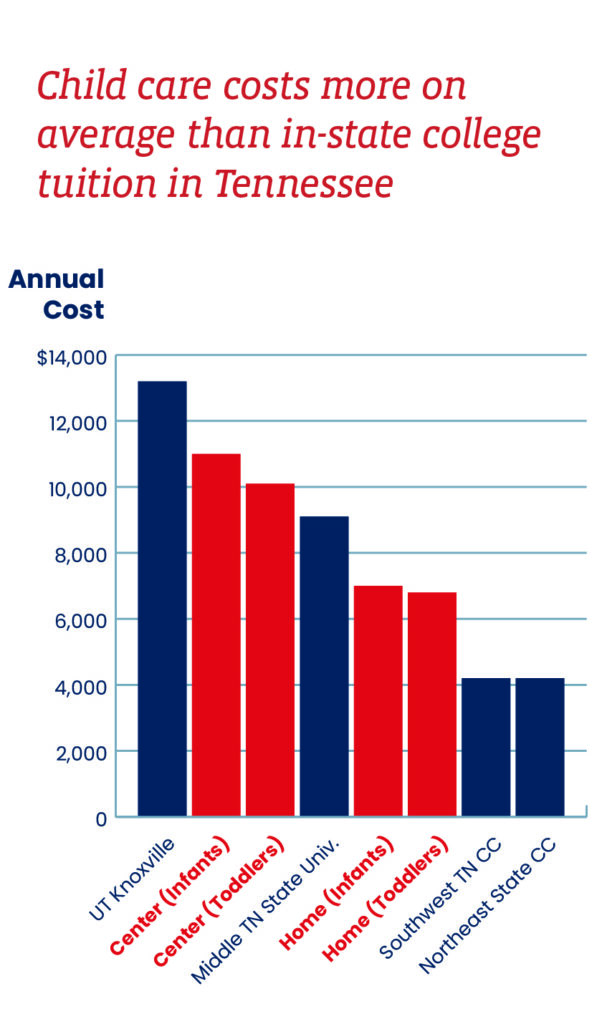

In Tennessee, the average annual price of center-based care, irrespective of quality, is $11,068 and $10,184for infants and toddlers respectively. For care in a home setting, the price is $7,194 for infants and $6,749 for toddlers.9 Child care costs more than most in-state college tuition.

Consider child care costs in light of Tennessee household income, and the affordability problem becomes clear. A third of Tennessee children under age 6 live in families with incomes below $40,000, and nearly half with incomes less than $60,000 annually.10 For reference, United Way’s ALICE report calculates $65,040 as a basic “survival” budget for a working family of two parents with an infant and preschooler.11

The Child Care Workforce Problem

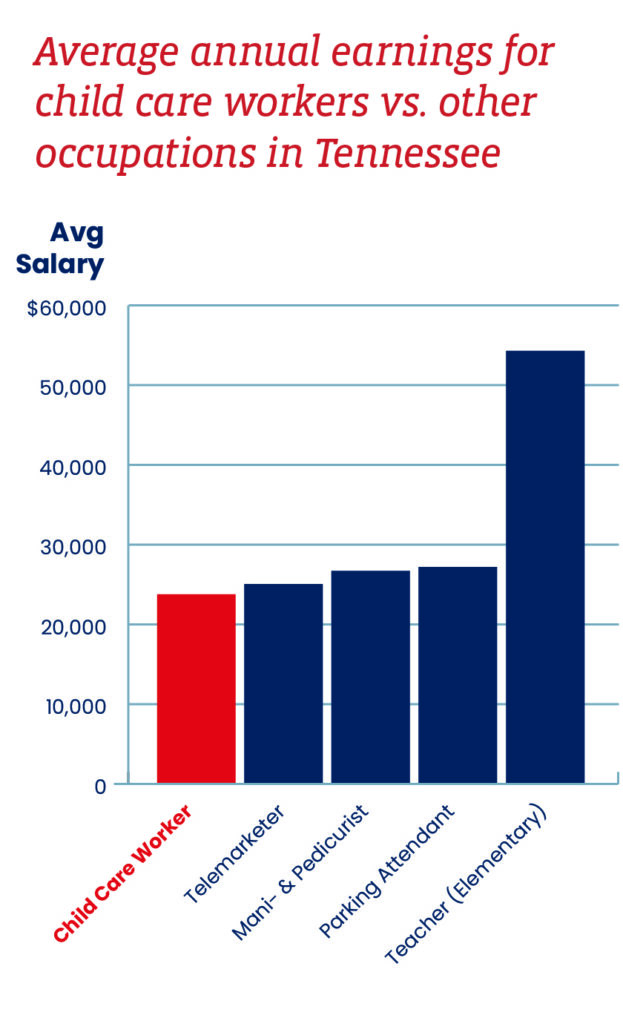

Child care providers struggle with balancing competitive workforce compensation with affordability for parents. The sad result is that the industry is among the lowest paying in Tennessee (and across the nation), thus adversely impacting supply, stability and quality of the child care workforce. The average annual pay for child care workers in Tennessee is $23,780 – less than that of parking attendants.12 Such low pay hurts workforce recruitment, causes high turnover, and discourages people from pursuing a career in the industry.13 The child care industry was failing to meet the needs of families before the pandemic.14 Now given the stresses of the pandemic on the child care workforce and other options for better pay, it’s no wonder the child care sector nationally has lost nearly 10 percent of its workforce compared to pre-pandemic levels.15 The child care labor shortage is exacerbating the problem of simple access to child care, while low pay often results in lower quality care.

Child care providers struggle with balancing competitive workforce compensation with affordability for parents. The sad result is that the industry is among the lowest paying in Tennessee (and across the nation), thus adversely impacting supply, stability and quality of the child care workforce. The average annual pay for child care workers in Tennessee is $23,780 – less than that of parking attendants.12 Such low pay hurts workforce recruitment, causes high turnover, and discourages people from pursuing a career in the industry.13 The child care industry was failing to meet the needs of families before the pandemic.14 Now given the stresses of the pandemic on the child care workforce and other options for better pay, it’s no wonder the child care sector nationally has lost nearly 10 percent of its workforce compared to pre-pandemic levels.15 The child care labor shortage is exacerbating the problem of simple access to child care, while low pay often results in lower quality care.

Child Care Supply Isn’t Responding to Market Need

Largely because of the tension between child care workforce compensation and affordability for parents, the child care business model is difficult. Add to that the needs of many working parents for care during nontraditional hours, and the industry’s challenge gets more complex. In many instances, even if parents could afford child care, the hours of operation may not align with parent work hours. A study by the Urban Institute found that 41.4 percent of children under age 6 in Tennessee have parents who work nontraditional hours (weekends, early mornings and evenings)16, yet most child care centers operate Monday through Friday and close their doors at 5:30 or 6 p.m.

Government and Business Investment in Child Care

Market forces alone aren’t sufficient to address the child care crisis. Neither are government or employer investments yet moving the needle substantially – but there is opportunity with both.

Government Financial Aid for Families is Limited, But New Strategies Are Emerging

The federal Child Care and Development Fund and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs, operated through the Tennessee Department of Human Services (TDHS), are the major sources of child care financial aid for low-income families. However, this tuition assistance reaches only a fraction of eligible families, and the tuition rates offered, while they have been increased recently, still aren’t sufficient to allow providers to pay their workforce competitively. TQEE’s parent survey indicated that only 8 percent of parents of children under age 6 are accessing this financial aid – and TDHS reports about 20,000 children from birth through age 12 participating in the programs.17

There are also about 20,000 children participating in federally funded Head Start programs across the state.18 And the state-funded Voluntary Pre-K (VPK) program operated by school districts is funded to serve roughly 18,000 children. These programs have limited availability, though wait lists and parent demand for them persist. Based on these numbers, one could reasonably estimate that in total, no more than about 20 percent of the 300,000 children under age 6 with all parents in the workforce receive some form of financial assistance for child care or early learning programs.

The Tennessee Child Care Task Force, though, will be releasing recommendations at the end of 2022 with guidance for new strategic investments which could make a good start toward improving access, affordability and quality of child care in the state. Furthermore, there is strong parent demand and advocate momentum for making the state’s VPK program an option for more families.

How Employers are Stepping Up To Challenges in Child Care

In today’s challenging labor market, employers are seeking new ways to recruit and retain employees, and are increasingly adding child care and family-friendly benefits as a solution.

In today’s challenging labor market, employers are seeking new ways to recruit and retain employees, and are increasingly adding child care and family-friendly benefits as a solution.

Child care has become a top HR trend in 2022.19 And 56 percent of employers now offer some child care benefits in 2022, according to Care.com’s “The future of benefits” report surveying 500 companies every year.20 By comparison, only 36 percent of companies offered child care benefits in 2019.

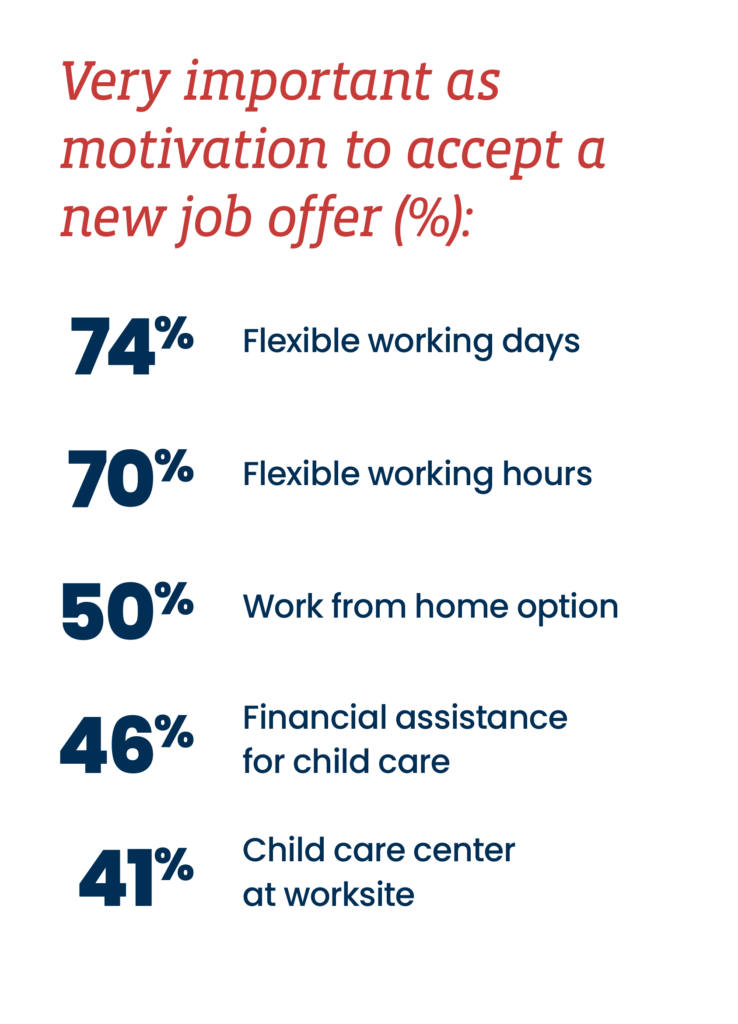

Employers are partnering with child care innovators. WeeCare for instance recently raised funding to scale child care benefits in partnership with employers and is working with many large companies such as JCPenney and Dollywood. Other innovators like Wonderschool, Kinside and Tootris are likewise partnering with employers to help solve their employees’ child care challenges.21 Those businesses investing in child care benefits can reap rewards such as cost savings from more successful recruitment and retention of employees. TQEE’s survey of working parents of young children revealed that child care and family-friendly benefits are very important in their employment decisions.

Child Care Tri-Share

Neither employer-sponsored child care nor government support are alone the solution. The greatest opportunity to solve Tennessee’s child care crisis is through partnerships where low- and middle-income families share the costs of high-quality care with employers and government.

Child Care Study Conclusion

The triple bottom line for high-quality child care

High-quality child care, which enables adults to work while laying a foundation for children’s success in school and beyond, is a powerful strategy for growing Tennessee’s workforce of today and tomorrow simultaneously.

The economics are clear: investments in high-quality care for working families will result in significant returns to taxpayers, businesses and family pocketbooks.

It’s time Tennessee made high-quality child care a priority strategy for building our state’s human capital.

Endnotes

1. Tennesseans for Quality Early Education, “Want to Grow Tennessee’s Economy? Fix the Child Care Crisis,” September 2019, http://tqee.org/app/uploads/2020/02/TQEE_TN_Final.pdf

2. For details on the economic analyses, see the accompanying technical report: “Economic Losses from Inadequate Child Care for Working Families in Tennessee,” December 2022, https://tqee.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/TQEE_2022_Technical_Report.pdf

3. U.S. Census Bureau, B23008 Age of Own Children Under 18 Years in Families and Subfamilies by Living Arrangements by Employment Status of Parents, 2021 American Community Survey, 1-year estimates

4. Harvard Center on the Developing Child, “Brain Architecture”. Retrieved December 2022 from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/

5. James J. Heckman and Tim Kautz, “Hard evidence on soft skills,” Labour Economics, August 1, 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3612993/

6. James J. Heckman and Dimitriy V. Masterov, 2007, “The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children,” Review of Agricultural Economics, American Agricultural Economics Association, Vol. 29(3) 446-493, 09.

7. Arthur J. Rolnick and Rob Grunewald, “Early Childhood Development on a Large Scale,” June 2005, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2005/early-childhood-development-on-a-large-scale

8. Harvard Center on the Developing Child, “Serve and Return”. Retrieved December 2022 from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/serve-and-return/

9. Permaul, B. (August 2021). Determining Child Care Market Rates in the State of Tennessee, FY2021. University of Tennessee, Boyd Center for Business and Economic Research. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/human-services/documents/2020-2021%20Market%20Rate%20Survey.pdf

10. U.S. Census Bureau, ACS 1-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample 2021

11. United Ways of Tennessee, ALICE Report. Retrieved from https://uwtn.org/106.5/alice

12. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Standard Occupational Classification Codes, May 2021. Retrieved on Oct 23, 2022, https://data.bls.gov/oes/#/geoOcc/Multiple%20occupations%20for%20one%20geographical%20area

13. Jennifer Ludden, “Poverty Wages for U.S. Child Care Workers May Be Behind Turnover,” National Public Radio, November 7, 2016, http://www.npr.org/ sections/health-shots/2016/11/07/500407637/povertywages-for-u-s-child-care-workers-maybe-behindhigh-turnover

14. Tennesseans for Quality Early Education, “Want to Grow Tennessee’s Economy? Fix the Child Care Crisis,” September 2019, http://tqee.org/app/uploads/2020/02/TQEE_TN_Final.pdf

15. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (national). Retrieved October 2022, https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CES6562440001

16. Urban Institute, Nontraditional hour care, 2021. https://www.urban.org/projects/state-snapshots-potential-demand-andpolicies-support-nontraditional-hour-child-care-30

17. Email from Gwen Laasar, TN Department of Human Services, to Blair Taylor on Friday, December 2, 12:43pm CT

18. Tennessee Department of Education website, “Head Start”. Retrieved October 2022 from https://www.tn.gov/education/early-learning/head-start.html

19. Brett Farmiloe, The SHRM Blog, June 27, 2022. https://blog.shrm.org/blog/the-12-biggest-hr-trends-in-2022

20. Care.com, “Future of Benefits Report 2022”, https://www.care.com/business/resources/ebooks-and-reports/future-ofbenefits-report-2022/

21. Isabelle Hau, “The Workforce of Tomorrow Requires A Child Care System Fit for the Future”, Forbes, August 2, 2022 https://www.forbes.com/sites/isabellehau-1/2022/08/02/the-workforce-of-tomorrow-requires-a-child-care-system-fit-for-thefuture/?sh=1e1f8d7a50cd